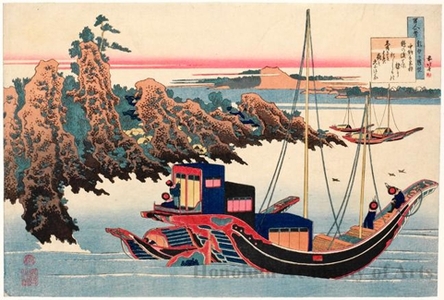

Katsushika Hokusai创作的日本版画《Chünagon Yakamochi (Ötomo no Yakamochi)》

标题:Chünagon Yakamochi (Ötomo no Yakamochi)

日期:c. 1835 - 1836

详情:更多信息...

来源:Honolulu Museum of Art

浏览所有5,476幅版画...

描述:

The print depicts a poet Otomo no Yakamochi’s poem “Magpie Bridge.” The poem refers to an old Chinese myth about a herdsman in love with a weaver maiden. As a result of not paying attention to his herd, the herdsman’s cattle ate all the flowers in the heavanly fields. The angry gods thus separated the two lovers with the Milky Way allowing them to meet only once a year by crossing a bridge created by the wings of magpies. The two lovers must part by dawn. Hokusai uses allusions to the dawn and to Chinese origins of the subject. The boat and the men are Chinese. The men point to three magpies that fly above the boat. The peninsula in the center appears suspended in midair as if it is a bridge linking the near bank of the river to the far one. The artist also includes ships in the early morning that are ready to do battle, and above it all, the red cliff. Hokusai added a village on the peninsula and much detail to the boat in the foreground. (from “100 Poems, One Poem Each” exhibition, 1/18/2005-) *************************** The Ogura Hyakunin Isshu, or “One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets for the Ogura District Residence,” was compiled by Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241) in the thirteenth century. He was requested to make the poetry anthology by his son, Fujiwara no Tame’ie, who may also have been involved in its completion. Composed by members of the imperial family and high ranking courtiers from the seventh through the thirteenth centuries, the poems are waka, literally “Japanese songs,” a form of court poetry consisting of thirty-one syllables arranged in five lines of 5, 7, 5, 7, 7 syllables each. Waka was the dominant form of court poetry in Japan at the time, a position it held until the advent of haiku in the seventeenth century. Teika’s work would become the most important compilation of classical Japanese poetry for centuries to come, remaining influential well into the modern era. Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) turned to literature for inspiration throughout his long career, beginning with luxurious, privately commissioned surimono prints designed for poetry clubs. He was also a prolific book illustrator, providing images for a wide range of works from contemporary Japanese fiction to Chinese classics. During his peak period of woodblock print publication in the 1830s, Hokusai produced two series of single-sheet prints dedicated to poets, True Mirrors of Poetry, a vertical series which included both Japanese and Chinese poets, and One Hundred Poems Explained by the Nurse, a horizontal series in which each sheet illustrated one of the poems in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. Together with the slightly earlier series, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, the One Hundred Poems series is considered to be the pinnacle of Hokusai’s work as a woodblock print designer. However, the One Hundred Poems series, which would have been Hokusai’s most ambitious series of single-sheet prints, was interrupted by the Tenpö famine of the mid-1830s, and never completed. Only twenty-eight prints (twenty-seven in full color and one in only keyblock impressions) are known to survive. The Academy is fortunate to have a complete set of the prints that were finished from the One Hundred Poems series, donated by James A. Michener. In conjunction with the major special exhibition Hokusai’s Summit: The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, in Gallery 28 from September 23, 2009 to January 3, 2010, all twenty-seven of the full color prints from the One Hundred Poems series are displayed in this gallery. After the 1830s, Hokusai turned his attention away from single-sheet woodblock prints, although he continued to produce books and to refine his painting skills until the end of his life. Consequently, the One Hundred Poems series, although incomplete, represents Hokusai’s last major accomplishment in this medium. Interestingly, Hokusai became increasingly preoccupied with the symbolism of the number one hundred in his later years, and after his first failed attempt to produce one hundred prints for the One Hundred Poems series, he went on to complete one hundred monochrome illustrations of Mount Fuji in three volumes of woodblock printed books (called One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji ), and he began to affix his paintings with a large seal reading hyaku, or “one hundred.” He aspired to become one hundred years old, at which point he predicted his art would be “divine.” Sadly, he passed away eleven years short of his goal, but he attained immortality as one of history’s most influential graphic designers, whose work continues to inspire artists around the world today. (from “One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets” exhibition, 10/08/2009-11/22/2009)

![The Hundred Poems [By the Hundred Poets] as Told by the Nurse: Chunagon Yakamochi (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki: Chunagon Yakamochi) Katsushika Hokusai, 葛飾北斎 (Katsushika Hokusai)创作的日本版画《The Hundred Poems [By the Hundred Poets] as Told by the Nurse: Chunagon Yakamochi (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki: Chunagon Yakamochi)》](https://data.ukiyo-e.org/scholten/thumbs/a8c0aaabd8834ca38e6da3211c10bba9.jpg)